Historia del Pensamiento y del Análisis Económico

U2. Desde los inicios hasta fines de la Edad Media

Contexto y “ubicación” de las ideas antiguas y medievales la economía

La concepción de lo que era “economía”

“Wealth consists not in having great possesions but in having few wants” [Epictetus]

“The value of money is not in its possesion, but in its use” [Aristotle]

“The wise man seeks balance in all things” [Lao Tzu]

We next have to consider the sins which have to do with voluntary exchanges…” [Aquinas, Summa Theologica (1948)]

La actividad económica en el mundo antiguo

- A diferencia de últimos 2 siglos, los pensadores antiguos se preocuparon por las consecuencias de ciertos tipos de actividades conómicas

- en aspectos como la justicia y la calidad de vida

- pocas se preguntaron por las causas de la conducta económica

- Estructura económica esencial de la sociedad prácticamente no cambió hasta fines del siglo XV

- economía de autosuficiencia \(\longrightarrow\) en su mayoría sin interacciones ni mercados

- Mecanismo de asignación de recursos no era descentralizado sino centralizado –autoridad gobernante

De la sociedad primitiva y tribal…

- La sociedad griega o incluso las descritas en el Antiguo Testamento poseían sólo algunas características del capitalismo moderno:

- propiedad privada; división del trabajo; mercados; y moneda

- Pensadores de aquella época emitieron juicios fragmentarios y esporádicos \(\longrightarrow\) reflejan no sólo las preocupaciones de la época sino también las primeras aproximaciones a conceptos económicos

- Preocupacion casi exclusiva por:

- cuestiones prácticas –aspectos técnicos del proceso como cambios de estación; fertilidad de la tierra; costumbres de los animales

- cuestiones morales –justicia, equiproporcionalidad [economía normativa]

… a la sociedad de clases y castas

- Aun en estadíos avanzados de estas sociedades, no se presentaba el problema específico económico-social que requiriera un abordaje analítico y técnico

- la relación esfuerzo-satisfacción de necesidades individuales era intuitiva y palpable a todo hombre ya que no había disociación entre producción y producto

- Eventualmente surgen tensiones entre:

- sociedad primitiva \(\longrightarrow\) propiedad comunal y actividad económica basica

- sociedad de clases y castas \(\longrightarrow\) propiedad privada y actividad económica más compleja

Los principales temas

- A modo general, se pueden mencionar 2 (dos) grandes orientadores del pensamiento en este largo período

- No especialización del análisis de la vida social \(\longrightarrow\) no separabilidad de la actividad económica del resto de las actividades (políticas, sociales). Esto fue una constante de autores de diversas extracciones y períodos

- Énfasis en cuestiones filosóficas generales \(\longrightarrow\) motivación detrás del estudio de temas como el comercio y los precios era evaluar la justicia y equidad

- Otro tema era la administración pública pero mayoritariamente dentro de un marco ético (normativo)

- No había marco científico en el sentido de Friedman (y desde la ciencia moderna)

Cobertura, alcance y profundidad

Selectividad y limitaciones

- Todo curso de HPE debe plantear algún criterio de selectividad en el material a cubrir y desarrollar. En los ultimos dos siglos y medio, cientos de pensadores han escrito miles de libros y artículos sobre teoría económica y el capitalismo

- Varios criterios posibles

- “importancia” \(\longrightarrow\) poco científico [¿qué y quién es importante?]

- conexión con eventos históricos –pastoreo, feudalismo, descubrimientos, revolución industrial, democratización, automatización –relación entre hechos sociales y teorías sociales

- separabilidad entre elementos “científicos” e “ideológicos” en diferentes autores

Ortodoxia versus heterodoxia

- Principales autores ortodoxos modernos se han enfocado casi exclusivamente en alguno/s de los siguientes temas: 1) asignación; 2) distribución; 3) estabilidad; y 4) crecimiento.

- Los autores heterodoxos en muchos casos se han enfocado en las fuerzas y razones que producen cambios en la sociedad y en la economía

- ortodoxos suponen dadas las instituciones sociales, políticas y económicas y estudian la conducta economica en esos marcos; heterodoxos han buscado explicar las fuerzas que llevaron a esas instituciones

- Diferencias en énfasis y alcance, no necesariamente paradigmas opuestos \(\longrightarrow\) enriqueceder estudiar ambos

Diversidad y representatividad

- Un tema relevante en cualquier historia del pensamiento económico es el de la diversidad y representatividad.

- Existe evidencia de actividad económica verificable desde tiempos muy remotos –esto se dio en diferentes geografías, diferentes culturas y diferentes personas

- sin embargo, gran mayoría de historias de las ideas económicas excluyen a algunas (todas) de estas geografías, culturas y personas

- Particularmente pensamos en la exclusion de autores orientales, de autores del hemisferio sur, de mujeres y de poblaciones indígenas y otras etnias

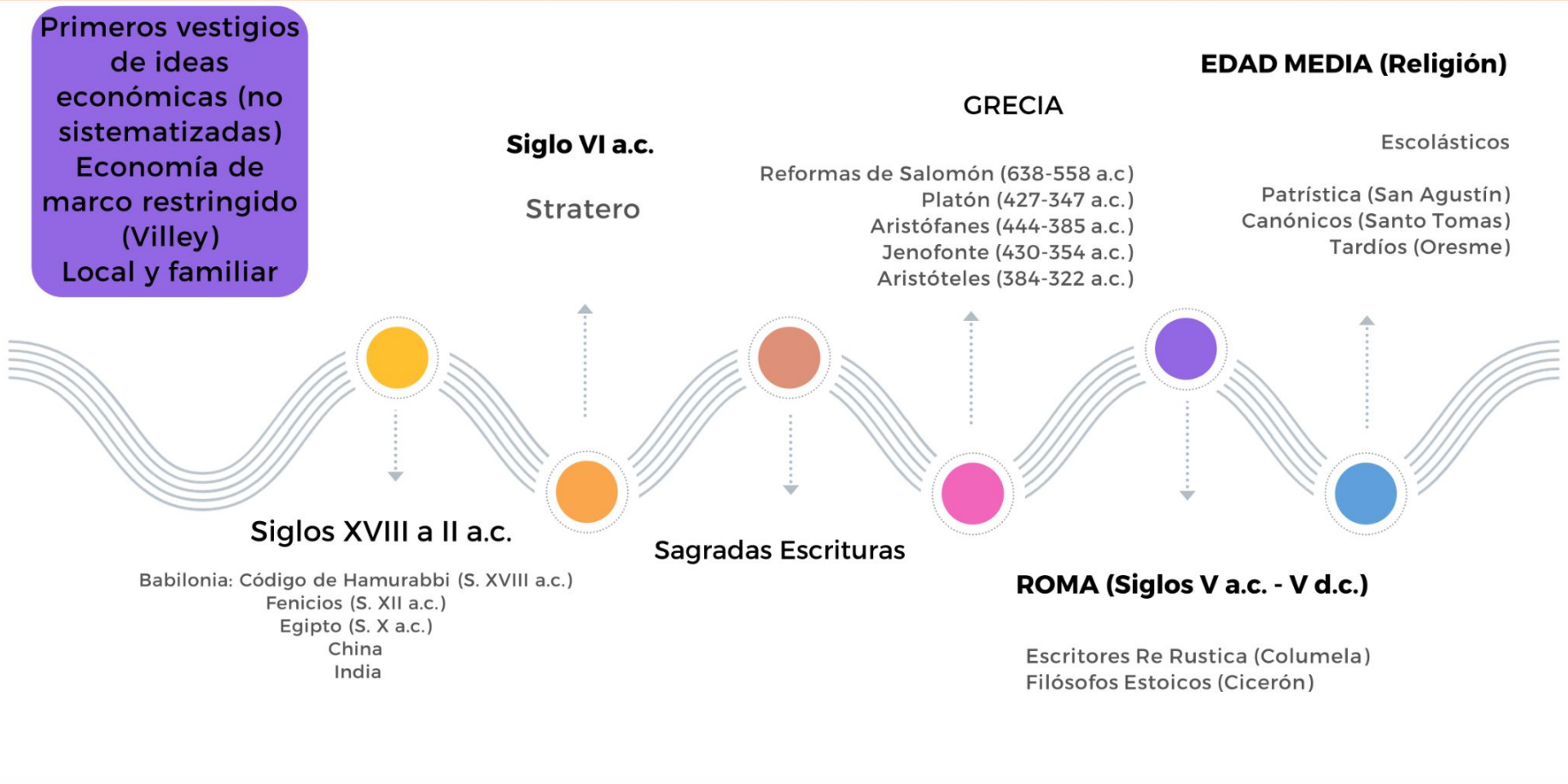

Usted está aquí:

Tradiciones y ramas

- La historia del pensamiento económico en la antigüedad y la Edad Media sienta las bases del desarrollo de la economía moderna.

- Siguiendo a Lowry (2003) podría estructurarse alrededor de tres tradiciones fundamentales:

- Administrativa – Organización económica basada en la gestión del Estado y la burocracia.

- Moral – Influencia de la religión y la ética en la economía.

- Analítica – Conceptos sobre valor, intercambio y especialización.

- Grecia, Roma, el mundo islámico y la Europa medieval aportaron enfoques distintivos a la evolución del pensamiento económico.

La tradición administrativa [2500 a.C.-100 a.C]

Características y naturaleza

- Los primeros registros de organización económica formal con sus marcos “intelectuales” correspondientes

- circa 2500 a.C. \(\longrightarrow\) civilizaciones fluviales en los valles del Nilo (Egipto) y Eufrates (Mesopotamia), principalmente con sumerios, asirios y babilónicos

- Período entre 1000 a.C. y 200 a.C. se dan los mejores registros que representan esta tradición

- época Clásica (Grecia) filosofía helenística; monarquía hebrea; dinastía Zhou Oriental y caída de la monarquía (China), imperio Maurya (India)

- Si bien combinaron elementos de las tres tradiciones, naturaleza y fundamento esencial de las ideas y escritos fue administrativa

Los primeros registros

- En las primeras civilizaciones, la economía era gestionada por el Estado.

- Civilizaciones fluviales (Egipto, Mesopotamia):

- Agricultura coordinada con inundaciones anuales.

- Graneros estatales y contabilidad centralizada para almacenar excedentes.

- Necesidad de medición de tierras y regulación pública.

- Ejemplo \(\longrightarrow\) relatos del Antiguo Testamento sobre José, quien administró graneros en Egipto para prevenir hambrunas.

Los primeros registros (cont.)

- Tablas de Erlenmeyer (2200 a.C., Sumeria) “descubiertas” en 1988:

- Registros de producción agrícola y eficiencia laboral.

- Introducción de sistemas contables avanzados.

- Influencia sumeria en Babilonia y mundo islámico:

- Paso de habilidades matemáticas, gráficas y administrativas

- desarrollo del sistema sexagesimal para cálculos administrativos.

- Uso del ábaco y registros contables como precursores de la contabilidad.

- Paso de habilidades matemáticas, gráficas y administrativas

Israel y la monarquía hebrea

- La monarquía hebrea unida y dividida (1047 a 722 A.C) ve introducción de propiedad privada y comercio interior y exterior

- nace la posibilidad de acumulación (Libro de los Reyes)

- Sociedad con marcada división entre ricos y pobres, incluso clase esclava

- Alta incidencia de derechos de peaje, impuestos elevados

- empobrecimiento de las masas y aparece por 1ra vez una clase desposeída

- Profetas (tradición moral) condenaban esto y excesos de las nuevas clases

- algunos logros \(\longrightarrow\) prohibición de embargar la ropa y utiles de trabajo

Antiguos griegos: características generales del pensamiento griego

- Visión antropocéntrica y administrativa –economía y administración del hogar

- El intercambio como mecanismo aislado \(\longrightarrow\) economía básica y simple

- Exaltaba areas como las artes militares y agricultura y tenían desprecio por el trabajo y el comercio y más generalmente la persecución del lucro y ganancia \(\longrightarrow\) prevalencia de consideraciones morales y éticas

- Aportes rudimentarios sobre varios temas: división y especialización del trabajo; utilidad subjetiva; dinero e interés; intercambio

- Poco y nulo rol del emprendedor y la creatividad –sociedad “congelada” sin dinámica económica y con rigidez de status político

Antiguos griegos: Hesíodo

- Hesíodo (circa 700-800 a.C) fue uno de los primeros griegos en esta tradición. Vivió en una comunidad con agricultura de subsistencia \(\longrightarrow\) preocupación principal escasez –recursos limitados versus necesidad ilimitadas – de ahí su preocupación por la eficiencia

- Obra principal \(\longrightarrow\) Works and Days (poema)

- Deseo de emulación (en consumo) estimula un espíritu de competencia

- aplicación de trabajo (crucial) y capital

- Podría intuirse una rudimentaria concepción del tradeoff trabajo-consumo \(\longrightarrow\) para sobreponerse a la escasez, mas trabajo era necesario a costa de menor tiempo de ocio

Antiguos griegos: Jenofonte

- Jenofonte (430-355 a.C.) fue filósofo, soldado e historiador. Escribió su obra más conocida, Oeconomicus donde trata varios temas:

- Organización de la producción agrícola.

- Importancia de la eficiencia y especialización.

- Se ocupó de temas prácticos aunque incursionó en filosofía moral.

- vestigios de utilitarianismo –“mejores acciones son las más beneficiosas para todos” e igualitarismo –“esposas y esposos deberían ser co-trabajadores en el hogar”

- concepción subjetiva (relativa) de utilidad

Antiguos griegos: Jenofonte (cont.)

The woman conceives and bears her burden in travail, risking her life, and giving of her own food; and, with much labor, having endured to the end and brought forth her child, she rears and cares for it, although she has not received any good thing, and the babe neither recognizes its benefactress nor can make its wants known to her; still she guesses what is good for it, and what it likes, and seeks to supply these things, and rears it for a long season, enduring toil day and night, nothing knowing what return she will get.

- Centró sus ideas en el individuo decisor-administrador

- un buen administrador es aquel que incrementa el tamaño del excedente

- División de las tareas del hogar es clave para él –límite: extensión del mercado

Antiguos griegos: Platón

- Uno de los más importantes fue Platón (428-348 a.C). Su obra principal en la temática es La República [“el alegato más elocuente en favor de una cierta clase de comunismo jamás escrito” Robbins (2000)]

- Describe a su Estado ideal: Platón creía que debía ser rígido y estático \(\longrightarrow\) todo cambio es regresivo [Platón repudiaba la democracia; alababa a Esparta y no a Atenas]

- Estructura de la sociedad

- Filósofos

- Soldados (“guardianes”)

- Trabajadores-productores

Antiguos griegos: Platón (cont.)

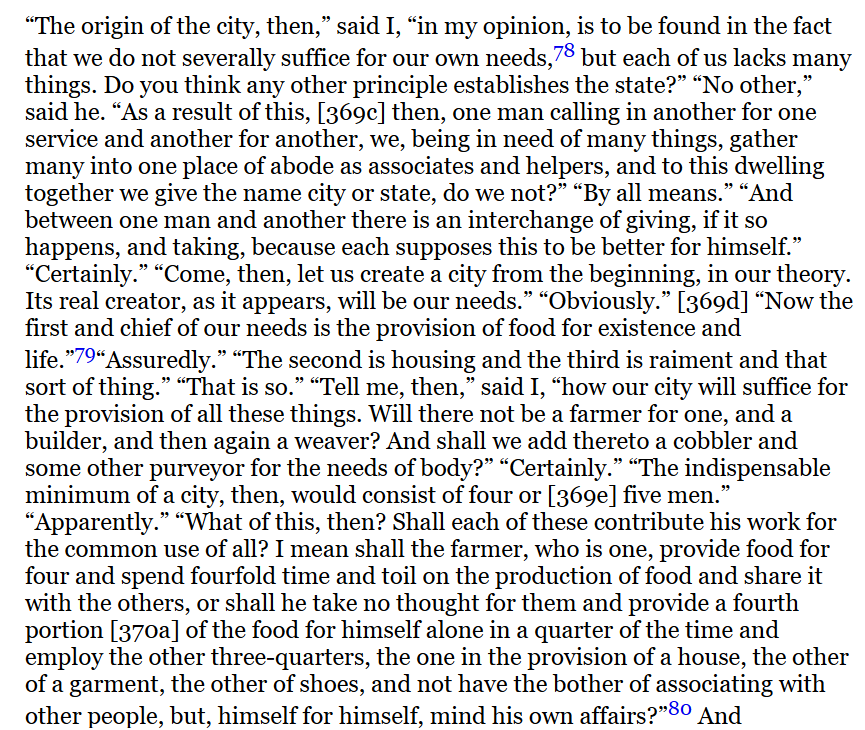

- Primer pensador occidental que menciona y analiza la importancia del principio de la división del trabajo \(\longrightarrow\) la especialización emerge a partir de la naturaleza humana en particular su diversidad y desigualdad

“We are not all alike; there are many diversities of natures among us which are adapted to different occupations”

- Diferencias son originarias no adquiridas –i.e. a través de la educación

- Dado que individuos diferentes producen bienes diferentes, la especialización da fundamento al comercio –además la especialización es el fundamento económico de la ciudad (polis)

Antiguos griegos: Platón (cont.)

- Denunciaba y despreciaba el uso de oro y plata como moneda –veía una amenaza a la regulación económica y moral de la polis

- Para concretar su utopía ordenada la sociedad de Platón debía ser rígida y estática

- poco espacio para la innovación, dinámica empresaria y crecimiento económico

- Incluso esto lo extendió al crecimiento poblacional \(\longrightarrow\) abogaba por mantener el número de ciudadanos constante en 5000 terratenientes!

Antiguos griegos: Platón (cont.)

Antiguos griegos: Platón (cont.)

Antiguos griegos: Protágoras

- A diferencia de Platón, Protágoras (480-411 a.C.) fue un relativista –no existe ninguna verdad objetiva sino sólo opiniones subjetivas.

- Todo está condicionado por el contexto, por el tiempo y lugar

El hombre es la medida de todas las cosas

- Defendió la importancia de apelar a las emociones en lugar de utilizar sólo la razón y la lógica

Antiguos griegos: Protágoras (cont.)

- Varios autores afirman que fue Protágoras (480-411 a.C.) quien acercó uno de los primeros antecedentes de la ideal del valor-trabajo y del individualismo subjetivo \(\longrightarrow\) idea del hombre-medida

- Además, identificó aunque de manera rudimentaria dos elementos importantes:

- el rol del mercado como asignador de recursos para maximizar utilidad

- el uso de la medición hedonística en la evaluación de la elección

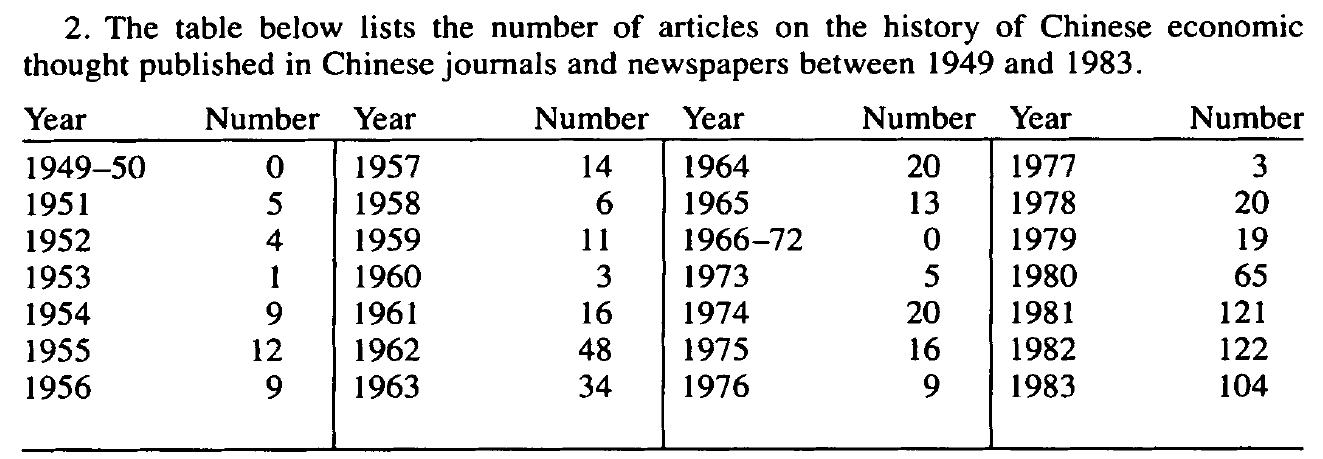

China y la tradición oriental

- Entre los años 771 y 249 a.C. se produjo en China un revolución a nivel de pensamiento económico coincidente con la caída de la autoridad monárquica

- Schumpeter sin embargo relativizó la importancia de la tradición oriental (similar a lo que pensaba de griegos y romanos)

- Autores más recientes cuestionan esto; “revival” interés luego de muerte de Mao.

- Cuatro escuelas principales trataron temas económicos: a) confucianistas; b) moistas; c) taoistas; y d) legalistas

- Según Schumpeter, sólo los legalistas trataron con temas prácticos y administrativos; el resto y sobre todo el confucianismo eraa más bien un sistema de valores éticos y morales.

China y la tradición oriental (cont.)

El renovado interés en la tradición oriental

China y la tradición oriental: Guan Zhong

- Guan Zhong [720-645 a.C.] principal pensador filosófia, economía y política

- filosofía del Qing Zhong –ligero, pesado- idea primitiva de \(O\) y \(D\)

- valor de todos los bienes es relativo

Qing 轻 means “light” and by extension “unimportant,” “inconsequential,” or “cheap.” It means to accord little or no value to something. Zhong 重 means “heavy,” and by extension “important”, “serious” or “expensive”. It means to value something. As a compound the two characters usually mean “weight”.

- Bienes pesados considerados esenciales (producción/bienestar); bienes ligeros son vistos como no esenciales

China y la tradición oriental: Guan Zhong (cont.)

- Anticipa la escasez como determinante del precio –“when things are plentiful, they will be cheap; when they are scarce, they will be expensive”

- Demanda influía sobre precio –además \(D\) como depósito de valor. Si un bien “se guarda bajo llave”, entonces tenderá a subir su precio

- Idea sobre estructura de mercado –“Goods if concentrated will become heavy, but will turn light once they are scattered about”

- Impuestos instantáneos afectan precio inmediatamente (“heavy”); impuestos graduales difieren efecto (“light”)

- Subsistencia dependía del valor de granos

- valor del dinero mueve en dirección opuesta al precio del grano (“numeraire”)

China y la tradición oriental: Guan Zhong (cont.)

- El rol de la política económica, según el Guanzi debía ser el de “pesar y balancear”, usar lo que es pesado para compensar lo que es ligero

- El gobierno debía comprar bienes cuando eran ligeros y venderos cuando eran pesados de manera de suavizar fluctuaciones \(\longrightarrow\) idea de política fiscal contracíclica

- Indicios de funcionamiento (descentralizado) del mercado

China y la tradición oriental: Guan Zhong (cont.)

“[a]s the harvest is bad or good, grain will be expensive or cheap. …if the prince is not able to control the situation, it will lead to large-scale traders roaming the markets and taking advantage of the people’s lack of things to increase their capital a hundredfold”

“it is the nature of men that whenever they see profit, they cannot help chasing after it”

India y la “ciencia de la riqueza”

- Algunos autores sugieren que hubo pensamiento económico no científico en la India particularmente en el tiempo del gran imperio unificado Maurya [322-185 a.C.]

- Kautylia (Chanakia) fue un filósofo y asesor del rey y escritor del principal tratado sobre asuntos económicos y políticos de la época

- el Arthasastra [“ciencia de la riqueza”] contiene 15 partes y secciones que discuten temas como códigos legales, política exterior, organización económica y sobre impuestos y gastos militares

- Premisa \(\longrightarrow\) el Estado (gobierno) juega un rol vital en mantener el status material tanto de la nación como de sus habitantes

India y la “ciencia de la riqueza” (cont.)

- Concepción religiosa de actividad económica y social \(\longrightarrow\) éxito material era no sólo moralmente deseable sino una etapa esencial en la vida civilizada

- persecución de ganancia no era incompatible con vida moral

- El gobierno del Rey debía ser activo la administración de la economía \(\longrightarrow\) política económica activa y grado importante de control estatal sobre la economía

- pero condición necesaria una “burocracia” eficiente y claramente definida

- Regulación estatal de casi toda actividad económica privada \(\longrightarrow\) Kautylia convencido de que se podía controlar comportamiento individual a través de incentivos (premios y castigos)

La tradición moral [750 a.C-500]

Características y naturaleza

- Economía influenciada por valores éticos y religiosos.

- Profetas hebreos \(\longrightarrow\) visión idealista y naive. Buscaban eliminar vicios y revertir a sociedad ideal –ie. cambios producto de “cambio en el corazón del hombre”

- Aristóteles y la economía justa:

- Diferenciación entre economía natural (necesidades básicas) y economía antinatural (acumulación de riqueza). Condena de la usura como inmoral.

- Doctrina cristiana \(\longrightarrow\) trabajo como castigo divino (Génesis); reegulación del comercio basada en la moral y la justicia social

Taoismo en China

- Escuelas taoístas en China

- Lao-tzu \(\longrightarrow\) no interferencia estatal en asuntos económicos. Gobierno mínimo.

- Chuang-tzu \(\longrightarrow\) discurso anti-estatista –i.e “anti-casta”

- Filosofía liberal y fuerte componente moral

“a petty thief is put in jail. A great brigand becomes a ruler of State”

Aristóteles: entre lo moral y lo analítico

- Postuló la idea de que sólo la propiedad privada le provee al individuo la oportunidad de actuar moralmente –i.e. practicar las virtudes de la benevolencia y filantropía. La compulsión de la propiedad comunal destruye esa oportunidad.

- A diferencia de Platón, no se opuso a la limitación individual de acumular propiedad privada –la educación serviría como autoregulador de tal deseo

Aristóteles: entre lo moral y lo analítico (cont.)

- Introduce distinción entre necesidades naturales y deseos artificiales -origina conceptos de intercambio natural e intercambio artificial y relación con el dinero

En el intercambio natural, el dinero es un medio para un fin mientras que en el intercambio artificial, el dinero es tanto un medio como un fin.

- Rechazó el intercambio artifical porque implicaba intercambio por la mera razón de ganar dinero (inmoral)

- venta minorista, comercio, transporte y contratación de trabajo

Aristóteles: entre lo moral y lo analítico (cont.)

- Contradicción entre lo analítico y lo moral \(\longrightarrow\) aplica a discusión del dinero

- facilitaba la producción y el intercambio; eliminaba problema de mutua coincidencia de necesidades; depósito de valor

- pero condenaba moralmente el préstamo de dinero (y el correspondiente pago de interés) como “artificial”

- facilitaba la producción y el intercambio; eliminaba problema de mutua coincidencia de necesidades; depósito de valor

- Esta contradicción también aplica de manera integral a su discusión de la crematística (chrématistiqué) \(\longrightarrow\) “el arte de adquirir o producir los bienes utilizados por la economía” (oikonomiké) –acción de usar las riquezas

Aristóteles: entre lo moral y lo analítico (cont.)

Por tanto, es evidente que hay un arte de adquisición natural para los que administran la casa y la ciudad. …Existe otra clase de arte adquisitivo, que precisamente llaman -y está justificado que así lo hagan- crematística, para el cual parece que no existe límite alguno de riqueza y propiedad. Muchos consideran que existe uno solo, y el mismo que el ya mencionado a causa de su afinidad con él. Sin embargo, no es idéntico al dicho ni está lejos de él. Uno es por naturaleza y el otro no, sino que resulta más bien de una cierta experiencia y técnica [Aristóteles, Política. Libro I, pp. 68]

Aristóteles: entre lo moral y lo analítico (cont.)

Ambos usos son del mismo objeto, pero no de la misma manera; uno es propio del objeto, y el otro no. Por ejemplo, el uso de un zapato: como calzado y como objeto de cambio. Y ambos son utilizaciones del zapato. De hecho, el que cambia un zapato al que lo necesita por dinero o por alimento, utiliza el zapato en cuanto zapato, pero no según su propio uso, pues no se ha hecho para el cambio. Del mismo modo ocurre también con las demás posesiones, pues el cambio puede aplicarse a todas, teniendo su origen, en un principio, en un hecho natural: en que los hombres tienen unos más y otros menos de lo necesario. De ahí que es evidente también que el comercio de compra y venta no forma parte de la crematística por naturaleza, pues entonces sería necesario que el cambio se hiciera para satisfacer lo suficiente. [Aristóteles, Política. Libro I, pp. 68]

Aristóteles: entre lo moral y lo analítico (cont.)

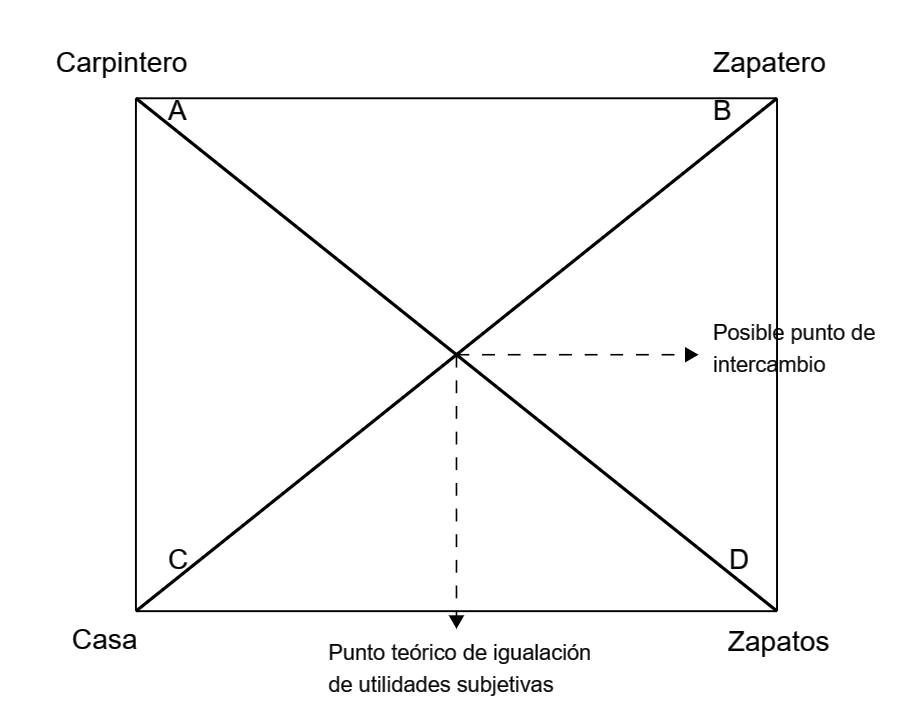

- Vio al intercambio como un proceso bilateral que genera ganancias para ambas partes –igualdad proporcionada, reciprocidad

- Distinguió entre valor en uso y valor en cambio (intercambio); sugirió que el segundo deriva (subordinado) del primero pero

- no ofreció ninguna teoría del valor de cambio (o del precio)

- Nueva instancia en que falla en separar lo moral de lo analítico en su tratamiento

- foco en problema ético de la justicia en el intercambio –justicia conmutativa

- principio de reciprocidad en el intercambio

- foco en problema ético de la justicia en el intercambio –justicia conmutativa

Pensamiento y filosofía griega: contexto

Los primeros filósofos-economistas

- Los antiguos griegos fueron la primer civilización en usar la razón para pensar sistemáticamente acerca del mundo que los rodeaba –usar lógica y obtener conocimiento verificable

- antes \(\longrightarrow\) tribus y pueblos bárbaros atribuían eventos naturales a los dioses

- Desarrollaron una teoría y método de razonamiento que eventualmente se denominó la ley natural

- análisis basado en ley natural gira alrededor de los conceptos de causa y efecto

La ley natural

La ley natural descansa en la idea de que ser necesariamente importa ser algo: alguna cosa o entidad. No existe el ser en el abstracto. Existen millones de entidades en el universo y cada una tiene su propia naturaleza –conjunto de atributos y/o propiedades que la distingue de otras. Se sigue que el hombre puede descubrir, estudiar e identificar de esta manera a las entidades. Dadas dos entidades \(X\) e \(Y\) con sus respectivas naturalezas, podemos averiguar qué sucede cuando estas entidades ineractúan. Por ejemplo, si \(X\) e \(Y\) interactuán en ciertas cantidades, obtenemos \(Z\) en cierta cantidad. Decimos que \(Z\) –el efecto- ha sido causado por la interacción de \(X\) e \(Y\).

- Sabemos que la interacción de dos moléculas de \(H\) y una molécula de \(O\) da por efecto una molécula de una nueva entidad, \(H_{2}O\) (efecto)

Los principios aristotélicos

Principio de la Identidad

Toda entidad es igual a si misma \(\longrightarrow\) \(\forall A, A=A\)

Principio de la No Contradicción

Una entidad no puede ser y no ser al mismo tiempo \(\longrightarrow\) \(\neg(A \wedge \neg A)\)

Principio del Tercero Excluido

Toda entidad debe ser o no ser \(\longrightarrow\) \((A \vee \neg A)\)

El individuo y la ley natural

- El individuo actúa –adopta valores y propósitos y formas de lograrlos y debe operar dentro de la ley natural

- las propiedades (naturaleza) de el mismo y de otras entidades y los modos en que interactúan

- Civilización occidental \(\longrightarrow\) encuentra sus orígenes en Grecia en las dos tradiciones filosóficas más importantes –Platónica y Aristotélica

- filosofía platónica \(\longrightarrow\) existencia ideal (verdadera naturaleza del individuo) –el individuo verdaderamente existente es eterno e infinito

- filosofía aristotélica \(\longrightarrow\) existencia contingente –limitada; no necesaria ni eterna (“sólo la existencia de Dios es necesaria y trasciende el tiempo”)

El individuo y la organización social

- Vida organizada en pequeñas ciudades-Estado (“polis”) cuyo gobierno estaba a cargo de una oligarquía de ciudadanos privilegiados. Mayoría de población eran esclavos o residentes extranjeros –sólo 7% tenían privilegios de democracia (“ciudadanos”) en Atenas

- Platón promovía regímenes despóticos; Aristóteles algo más moderado

- la virtud y la buena vida basadas alrededor de la polis no del individuo [polis over individual]

- visión intrínsecamente estatista y elitista

- Doctrina clásica de “ley natural” influyó en pensamiento cristiano y medieval

- no evolucionó en la doctrina del “derecho natural” de siglos 17 y 18

La tradición analítica [750 a.C.- 500]

Características y naturaleza

- Schumpeter argumenta que hay poco y nada rescatable en la línea analítica en toda la historia hasta el siglo XVII-XVIII

- en particular, hubo una carencia importante de análisis económico en el sentido moderno

- adicionalmente y en su gran mayoría, el razonamiento economico estuvo imbuido de una gran carga moral y ética [economía normativa]

- No obstante hubo algunos autores y tradiciones destacaron al intentar un abordaje analítico -se acercaron a una tradición rigurosa de análisis economico.

Temas y conceptos principales

- Conceptos de valor y precio:

- Aristóteles diferencia entre valor de uso y valor de cambio.

- concepto de precio justo

- Introducción de especialización productiva.

- Aristóteles diferencia entre valor de uso y valor de cambio.

- División del trabajo en la antigüedad:

- Platón y la especialización como base de la economía.

- Introducción de dinero, préstamos e interés

- origen y evolución del dinero

El Filósofo: Aristóteles

- Discípulo (y antagonista) de Platón –Platón es mi amigo, pero más amiga es la verdad

- Largamente más influyente que Platón en temas filosóficos y otras areas:

- estructura de pensamiento fue dominante en tradición occidental hasta siglos 16 y 17 –ideas políticas y morales

- Dos grandes obras, entre muchas, fueron Etica y Política. Su pensamiento filosófico lo hizo preocuparse por lo natural y lo justo

- Ofrece ideas y discusiones aisladas; no teoría del valor y/o distribución.

El Filósofo: Aristóteles y la propiedad privada

- Una diferencia radical con Platón fue en relación a la institución de la propiedad privada la cual favoreció [en contra del comunismo platónico] –el objetivo de perfecta unidad de Platón iba en contra de la diversidad de la humanidad y en contra de las ventajas recíprocas del intercambio.

- La propiedad privada es más productiva que la propiedad comunal y conduce a mayor progreso

- La propiedad comunal inherentemente conduce al conflicto interpersonal–problema del esfuerzo individual relativo a lo obtenido [¿free rider?]

- La propiedad privada está implantada en la naturaleza humana

- La propiedad privada ha existido siempre y en todos lados

El Filósofo: Aristóteles y el dinero

- Comprendió y destacó las funciones del dinero: 1) patrón de valor, 2) medio de cambio y 3) depósito de valor. El dinero era en sí una commodity –existía un mdo. de dinero [valor en cambio]

- No entendió y/o no indagó en las razones económicas por las cuales existía el interés!

El Filósofo: Aristóteles y el intercambio

La existencia misma de cualquier sociedad no comunista involucra e intercambio de bienes y servicios. Inicialmente esto se da a través de trueque; pero esto no siempre es posible, o tiene un limite. Esto implicará que eventualmente los intercambios se realizarán a través de alguna commodity como medio de cambio sugirio que algunas commodities cumplian mejor ese rol –metales. Asimismo, por el requerimiento de su regla de equivalencia en el intercambio, se seguía que esta commodity tambien sería usada como medida de valor. Y finalmente reconoció, al menos implícitamente, su rol como depósito de valor –gran antecedente casi 2500 años antes de las discusiones en siglo XIX

- condiciones primitivas \(\longrightarrow\) trueque no necesita dinero; eventualmente \(\longrightarrow\) se produce intercambio indirecto –mediado por algo que sirva como dinero

El Filósofo: Aristóteles y el intercambio (cont.)

- Este pasaje plantea numerosos interrogantes e inconvenientes [¿ratio de constructor a zapatero? ¿comparación de ratios de profesiones a productos? ¿unidades de medición?]

This is why all things that are exchanged must be somehow comparable. It is for this end that money has been introduced, and it becomes in a sense an intermediate; for it measures all things, and therefore the excess and the defect – how many shoes are equal to a house or to a given amount of food. The number of shoes exchanged for a house (or for a given amount of food) must therefore correspond to the ratio of builder to shoemaker. For if this be not so, there will be no exchange and no intercourse

El Filósofo: Aristóteles y el intercambio (cont.)

Now proportionate return is secured by cross-conjunction. Let A be a builder, B a shoemaker, C a house, D a shoe. The builder, then, must get from the shoemaker the latter’s work, and must himself give him in return his own. If, then, first there is proportionate equality of goods, and then reciprocal action takes place, the result we mention will be effected. If not, the bargain is not equal, and does not hold; for there is nothing to prevent the work of the one being better than that of the other; they must therefore be equated.

El Filósofo: Aristóteles y el intercambio (cont.)

El Filósofo: Aristóteles y el intercambio (cont.)

- Aceptó precios de los bienes observados en mercado como estándares de su justicia conmutativa pero…condenó precios de monopolio

- Incurrió en el problema de aceptar todo intercambio que sucediera a los precios competitivos como justa [influencia sobre Escolásticos]

- otro problema \(\longrightarrow\) valor justo de un bien es “objetivo” sólo en el sentido que individuos no pueden alterarlo

- No hay elementos objetivos ni explícitos en sus escritos que acrediten que entendió las causas del valor de los bienes –observó los intercambios y ofreció una interpretación [¿justificación?]

El Filósofo: Aristóteles y el intercambio (cont.)

- Aristóteles no ofrece ninguna teoría del valor; no habla de contenido de horas de trabajo; no existe forma de determinar los valores de los productores; y tampoco el ratio

- Planteo de buscar un elemento de justicia en la determinación de precios lo llevó a exponer el principio de reciprocidad entre lo que el hombre da y recibe

- Debe haber pensado en algun valor objetivo (absoluto) de las cosas, algo intrínseco e inherente que es independiente de las circunstancias y/o de las valuaciones humanas

Roma y la teoría del mercado

- Derecho romano y contratos:

- Regulación de transacciones y obligaciones comerciales.

- Economía imperial:

- Tributación sobre tierras como fuente de ingresos.

- Legado en la economía moderna:

- Influencia en la regulación financiera y contractual.

Roma: principales contribuciones

- Gran contribución del imperio romano no económica \(\longrightarrow\) el derecho

- El ius gentium suministro marco legal para la actividad económica contemporánea y posterior

- Pensamiento cristiano primitivo se centró en el recto uso de bienes materiales (moral)

- Autores cristianos indiferentes respecto del análisis positivo

- Llamativa ausencia y escasez de pensamiento económico durante la Roma Republicana e Imperial y también durante la Cristiandad

Schumpeter, the Great gap [700-1200] y las ideas económicas medievales

La tesis de the Great gap

So far as our subject is concerned we may safely leap over 500 years to the epoch of St. Thomas Aquinas (1225-74) whose Summa lkeologica is in the history of thought what the southwestern spire of the Cathedral of Chartres is in the history of architecture [Schumpeter, 1954]

- Probablemente una de las definiciones más polémicas en la historia del pensamiento económico, su tesis del “Great Gap” de unos 500 años entre la caída de la civilización griega y los escritos de Santo Tomás de Aquino

- recientemente cuestionada y actualizada con autores aludiendo a varias contribuciones e ideas aportadas por pensadores árabes e islámicos

La decadencia secular de Occidente

- Occidente entra en la denominada Edad Oscura luego de la caída del último emperador romano [476 hasta siglos XII-XIII]

- contrapartida \(\longrightarrow\) auge y desarrollo del Islam y Oriente en ciencia e innovaciones [numeración arábica]

- Pero más importante aún \(\longrightarrow\) reintroducción de Aristóteles en Occidente

- Traducción de los textos y reintroducción de ideas de los griegos en período 1000-1500

¿Algunas luces en la Edad Oscura?

- Varios autores critican a Schumpeter por ignorar contribuciones de autores islámicos –asimismo, no hubo discontinuidad en los eventos históricos pero si en el pensamiento económico

- Ibn Kaldún [1332-1406] fue historiador, sociólogo y economista árabe con ideas que se anticiparon a varias teorías económicas

- teoría de la cohesión social \(\longrightarrow\) la prosperidad económica depende del grado de cohesión social, el que disminuye a medida que las sociedad se vuelven mas ricas

Pensamiento económico islámico

- Anticipó teoría del valor trabajo \(\longrightarrow\) sugirió que el trabajo era la fuente de todo valor y el esfuerzo humano determina la riqueza de un país

- también enfatizó los beneficios de la división del trabajo y especialización

- Determinación de precios a través de oferta y demanda \(\longrightarrow\) reconoció que la escasez aumenta el valor

- Poca y nula actividad estatal en la economía; en particular se opuso a la imposición excesiva

- naturaleza cíclica del crecimiento económico \(\longrightarrow\) versión primitiva de ciclos económicos

Economía e instituciones económicas medievales

- Feudalismo y economía \(\longrightarrow\) producción basada en la propiedad de la tierra.

- Servidumbre y producción agrícola autosuficiente.

- Monasterios y economía:

- Los monjes cistercienses innovaron en agricultura.

- Administración eficiente de tierras y recursos.

- Corporaciones y gremios:

- Regulación del comercio y la calidad de los productos.

Economía e instituciones económicas medievales (cont.)

- Feudalismo esencialmente un sistema de producción y distribución compuesto por el monarca, los señores y los siervos

- Propiedad=usufructuo. El feudo se convirtió en sede del poder político

- Actividad básica de autosuficiencia \(\longrightarrow\) comercio era o bien limitado o prohibido

- (Larga) transición a mercado como fenómeno de la vida diaria \(\longrightarrow\) de a poco a actividad económica se iba concentrando en centros comerciales

Surgimiento y evolución del comercio

- Comercio islámico:

- Expansión del comercio a través del Mediterráneo y rutas comerciales globales.

- Uso de cartas de crédito y cheques (sakk).

- Bancos y crédito medieval:

- Monti di Pietà y préstamos sin usura.

- Desarrollo de letras de cambio.

Surgimiento y evolución del comercio (cont.)

- Ferias comerciales medievales:

- Centros de comercio e intercambio financiero.

- Primeros bancos:

- Casas bancarias en Florencia y Venecia.

- Orígenes del capitalismo:

- Crecimiento de los mercados urbanos.

La escolástica y los doctores escolásticos

Las preocupaciones de los filósofos morales

- Se produce un cambio en las principales motivaciones de los filósofos morales de la época

- se concentraron básicamente en las obligaciones del individuo \(\longrightarrow\) ¿qué debería hacer el hombre Cristiano? [note que se estaba recién produciendo la transición a los Estados modernos]

“We next have to consider the sins which have to do with voluntary exchanges…” [Aquinas, Summa Theologica (1948)]

El método escolástico

- La tradición escolástica contribuye a preservar y desarrollar las ideas aristotélicas

- El metódo escolástico consistía básicamente en \(\longrightarrow\) se formulaba un tema y se detallaban las opiniones a ser reevaluadas. Se examinaban y ponderaban las opiniones contrarias y se producía un documento. Basado en la fe y peso de autoridad

- El principal interés de la clerecía era la justicia –no el intercambio.

- Los teóricos de la escolástica no escribieron ni se refieron centralmente a los temas económicos –solo aparecieron incidentalmente cuando había algún tema de justicia involucrado

La principal preocupación: el precio justo

- El centro de gravedad de la discusión sobre el valor y el intercambio en los teólogos del medioevo era el justo precio

- ¿Qué es y cómo se interpreta el justo precio?

- El justo precio era un precio que, tomando en cuenta la cantidad de trabajo incorporada, permitía mantener un status en un sistema de jerarquía

- La industria debía organizarse en base gremios mercantiles –asociaciones de productores y consumidores que velaban para que se cobrara el justo precio

La evaluación schumpeteriana de la escolástica

- Algunos autores rescatan las figuras de San Bernardino de Siena y San Antonino de Florencia [de Roover (1967)]

- idea de que la doctrina del precio justo deriva de una declaración de un tal Heinrich von Langenstein [una figura menor aunque ciertamente oscura y polémica en la tradición escolástica]

- “si las autoridades no fijan el precio, entonces el productor no debería cobrar no más que lo que le permitiría mantener su status en la jerarquía”

- idea de que la doctrina del precio justo deriva de una declaración de un tal Heinrich von Langenstein [una figura menor aunque ciertamente oscura y polémica en la tradición escolástica]

- Para von Langenstein la intervención y regulación de precios sería más efectiva que la determinación del justo precio en forma descentralizada

Los escolásticos principales: Santo Tomás

- La principal y más importante figura del movimiento escolástico fue Santo Tomás de Aquino

- Sus discusiones sobre “los pecados” en torno a los intercambios voluntarios no son muy coherentes y además rodeados de cierta imprecisión conceptual –no se sabe si refiere al intercambio aislado o al intercambio orgnaizado similar al de un mercado

Santo Tomás y el justo precio

- Referencia a San Agustín alabando el comportamiento de alguien que a quien ofrecen un libro a un precio debajo del que presumiblemente se podría haber obtenido y que se rehusa a pagar ese precio y ofrece uno más alto

- Pero en general los autores estudiosos de los escolásticos coinciden en que cuando Santo Tomás se refiere al intercambio organizado (no aislado), el justo precio para él es una estimación del precio pagado en un mercado relativamente competitivo

Santo Tomás y el justo precio (cont.)

- Argumenta que no es “un pecado” vender al precio vigente aún a sabiendas que hay más vendedores potenciales entrando al mercado (y que bajarán el precio) –pero encuentra virtuoso el hecho de comunicar esta información

- Santo Tomás parece formular una teoría de la demanda basada en las necesidad humanas (indigentia) y en principios morales

Santo Tomás y el justo precio (cont.)

- Reafirma la doble medida de los bienes: valor de uso y valor de cambio

- Introduce la necesidad en la fórmula del precio: *el precio varía con la necesidad

- El regulador del valor es la indigentia –en cierto modo precursor temprano de la teoría de la utilidad marginal

- Introdujo la idea de que el resultado del mercado no necesariamente es justo: justo precio (normativo) como opuesto al precio de mercado (positivo)

San Bernardino de Siena

- A diferencia de Santo Tomás (y Aristóteles), San Bernardino encuentra de utilidad el comercio y la industria. Pero critica fuertemente las trampas y la competencia desleal a veces usadas por mercaderes

- Sigue a Aristóteles (en oposición a Platón) sobre la propiedad privada \(\longrightarrow\) como la mejor forma de ser usada y aprovechada, en comparación con propiedad comunal

San Bernardino de Siena (cont.)

- Santo Tomás contrastó el valor de los ratones (vivos) y perlas (muertas) pero no formuló de manera explícita teoría alguna sobre valor de las cosas

- San Bernardino, en cambio, ofreció 3 (tres) elementos que determinaban el valor:

- la utilidad intrínseca del objeto

- la escasez del objeto

- la deseabilidad del objeto

- Note \(\longrightarrow\) en términos de la teoría de valor moderna, la distinción entre 1 y 2 no tiene ninguna relevancia

San Bernardino de Siena (cont.)

El cruel destino de Pierre Olivi. Casi un siglo antes que San Bernardino, un religioso francés y franciscano se había anticipado a San Bernardino casi por completo en temas de valor y utilidad. Cuenta la leyenda que San Bernardino omitió citar el trabajo de Olivi no por despistado sino por remordimiento: Olivi fue declarado hereje y sus huesos fueron desenterrados y esparcidos a los cuatro vientos.

San Bernardino de Siena (cont.)

- La utilidad intrínseca no es un factor absoluto –“de otra manera, un vaso de agua sería prácticamente impagable…pero es abundante” [paradoja del valor]

- El precio se determina por estimación colectiva \(\longrightarrow\) no es otra cosa que valuación de mercado

- Condena en toda ocasión las prácticas monopólicas

- Sobre salarios \(\longrightarrow\) aplican las mismas reglas que para los precios

El interés y la usura

- Existió un acuerdo casi total entre los escolásticos y sobre todo los tardíos en la condena (aristotélica) de la usura

- La discusión está presente en la Pregunta 78 de la Summa Theologica bajo el nombre “Of the Sin of Usuary Which Is Committed in Loans”

- La oposición era no a la ganancia de las sociedades

- La oposición era inflexible a cobrar interés sobre el dinero dado como préstamo

El interés y la usura (cont.)

(In proof of this,) it should be noted that there are some things the use of which is the consumption of the things themselves; as we consume wine by using it to drink and consume wheat by using it for food. Hence, in case of such things, the use should not be reckoned apart from the thing itself; but when the use has been granted to a man, the thing is granted by this very fact; and therefore, in such cases, the act of lending involves the transfer of ownership (dominum). Therefore, if a man wished to sell wine and the use of the wine separately, he would be selling the same thing twice, or selling what does not exist; hence he would obviously be guilty of a sin of injustice. For analogous reasons, a man commits injustice who lend wine or wheat expecting to receive two compensations.

El interés y la usura (cont.)

There are some things, however, the use of which is not the consumption of the thing itself; thus the use of a house is living in it, not destroying it. Hence, in such cases, both may be granted separately, as in the case of a man who transfers the ownership of a house to another, reserving the use of it for himself for a time; or, conversely, when a man grants someone the use of a house, while retaining the ownership. Therefore a man may lawfully receive a price for the use of a house, and in addition expect to receive back the house lent.

El interés y la usura (cont.)

- Increíblemente \(\longrightarrow\) el propio filósofo se refuta a si mismo en el párrafo siguiente!

- Si uno paga por el vino inmediatamente cuando se bebe, entonces no se paga interés, sólo se paga el precio del vino

- Pero si se bebe el vino y uno no paga por un año, la situación es la misma que la de un hombre que acepta una casa en préstamo por un año y no paga alquiler sino hasta el final del año!

- Había sólo una excepción cuando se toleraba \(\longrightarrow\) damnum emergens / lucrum cessans

- Hacia el siglo XIV y XV, dado el gran desarrollo de negocios y actividad mercantil, empieza a relajarse esta oposición a la usura

El interés y la usura (cont.)

- La Iglesia condenó la usura y durante la Edad Media hubo una prohibición absoluta. Las leyes contra la usura eran respaldadas por los gobiernos

- Sin embargo, ciertas formas de actividad comercial y societaria gozaban de formas legítimas del cobro de intereses. La doctrina entró pues en conflicto con la práctica

- La condena de la usura por parte de la Iglesia puede haber respondido a motivos egoístas, de modo de mantener su posición social de monopolio y abaratar así el costo de sus fondos.

Otros escolásticos: Enrique de Frimaria [1245-1340]

- Concibe a la indigentia como una medida agregada de “demanda frente a escasez”. Extendió el análisis tomista en favor de la demanda agregada \(\longrightarrow\) necesidad común de algo que es escaso

- La indigentia no elevaría el precio siempre y cuando hubiera abundancia

- Principal problema subsistía \(\longrightarrow\) los seguidores de la tradición aristotélica no lograron separar la demanda y la oferta como elementos en la fórmula del valor

Otros escolásticos: Jean Buridan [1300-1358]

- Acercó los conceptos de indigentia con el de demanda efectiva

- Distinguió entre necesidad individual y necesidad agregada; relacionó el valor a esta última. La conjunción de un número de consumidores contribuye a la formación de un precio justo de mercado (y normal)

- Transforma el concepto de necesidad por uno más amplio de deseo. Sienta las bases de la teoría de utilidad del siglo XIX

Otros escolásticos: Odonis y Crell

- Tradición escolástica se acercó bastante a lo que se conoce como la síntesis neoclásica aunque falló en reconocerla y proponerla explícitamente

- Odonis desarrolló una teoría del trabajo sobre diferencias de habilidades

- Crell logró incoporar estas ideas y agregó las de Buridan sobre demanda efectiva

- Sin embargo el problema de la determinación del valor no se resolvería hasta s. XIX

- Dos principios legados:

- trabajo como regulador del valor, si se gasta en algo útil

- todo trabajo siempre es escaso