U3. La economía pre-clásica. La transición a las ideas liberales. La fisiocracia

Historia del Pensamiento y del Análisis Económico

La transición liberal y los primeros “padres fundadores”

El siglo XVII

Fue uno de los siglos claves y mas trascendentales en la historia de la humanidad. La terrible brutalidad de la Guerra de los 30 Años (población en muchos países cayó en 50% o más) contrastó con los increíbles avances en las ciencias naturales. Se formaron las primeras sociedad científicas (Royal Society en UK). Esto marca también un quiebre esencial en relación a El Filósofo –tanto en Francia (Descartes) como en UK (Hobbes, Locke) lideraron un movimiento de revulsión respecto de la dominancia de Aristóteles. El cambio es significativo en muchos aspectos pero uno, que nos concierne, es relevante: el cambio en el estilo de la escritura

Los impulsores de las ideas económicas en la transición

- En esta larga transición hacia la economía científica, la gran mayoría de autores y pensadores que contribuyeron ideas, nociones y pensamientos sobre temas económicos pueden ser catalogados en dos grupos:

- Políticos/administradores (“consultant administrators”)

- Panfletistas

- Los primeros comprendían esencialmente funcionarios y personas vinculadoas con la administración; personas de praxis, carecían de los hábitos sistemáticos y la erudición del profesional académico.

Los impulsores de las ideas económicas en la transición (cont.)

- Los panfletistas eran en cambio una fauna diversa –proyectistas, emprendedores, lobbistas, planificadores, y hombres interesados por los problemas de la epoca

- Florecieron gracias en parte al desarrollo de la imprenta. Con el advenimiento de los periódicos en siglo 17, dio nuevo impulso a este tipo de publicaciones

- La mayoría de los panfletistas sólo reflejaban humor y discusión de epoca, sin método ni rigor; algunos contribuyeron dosis de caracter estrictamente científico; incluso más, algunos pocos tuvieron notable capacidad para adelantarse a lo que se venía

Los precursores del economía política

- Un grupo de autores que caen en alguno (o en el medio) de los dos conjuntos dados arriba tuvieron el suficiente peso específico como para estudiarlos como parte esencial de la transición a las ideas económicas del siglo 18.

- En primer lugar, dos figuras importantes que estuvieron a las puertas del carácter científico de la economía fueron William Petty y Richard Cantillon

- Petty (Marx) y Cantillon (Jevons) han sido considerados por los padres fundadores de la economía política

- En segundo lugar, La fisiocracia fue la otra manifestación de que la transición entre la economía pre-científica y científica estaba madurando

Los primeros econometristas

- Si bien no formaron parte de ninguna escuela, uno de los criterios para agrupar a estos pensadores (“consultores-administradores”) es que tuvieron algo en común: el espíritu para el análisis númerico

- Es por ello que Schumpeter los considera como econometristas; de hecho, alude a que su trabajo describe a la perfección el trabajo de un econometrista

- Petty, Cantillon, Boisguillebert y Turgot entre los más importantes

Los inicios de la estadística: la aritmética política

- Durante los siglos 17 y 18, especialmente en Alemania, surgió y se popularizó un método de enseñanza que se especializaba en una presentación puramente descriptiva de los hechos relevantes para la administración pública [Conring, Achenwall]

- Estas estadísticas era primitivas, no guardaban relación con lo que hoy se conoce como métodos estadísticos \(\longrightarrow\) presentaban hechos no numéricos principalmente

- sin embargo, el propósito era esencialmente el mismo

- “ilustración de las condiciones y prospectos de la sociedad”

- sin embargo, el propósito era esencialmente el mismo

- Pero no fueron los profesores alemanes quien dieron curso e impulso decisivo a estos desarrollos

Sir William Petty [1623-87]

Un economista atípico y singular

El trabajo por tanto, no es la fuente única de los valores de uso que produce, de la riqueza material. El trabajo es el padre de ésta, como dice William Petty, y la tierra, su madre [Karl Marx El Capital, Libro I(1867)]

The method I take to do this is not yet very usual; for instead of using only comparative and superlative Words, and intellectual Arguments, I have taken the course (as a Specimen of the Political Arithmetic I have long aimed at) to express myself in Terms of Number, Weight, or Measure; to use only Arguments of Sense, and to consider only such Causes, as have visible Foundations in Nature. [Hull The Economic Writings of Sir William Petty (1899)]

Sir William Petty [1623-87]: el primer influencer

- Petty fue un ejemplo arquetípico del self-made man. Hijo de un sastre pobre en el sur de Inglaterra, se formó y desempeñó como médico, cirujano, matemático, ingeniero teórico, miembro del Parlamento, servidor público y empresario.

- Pasó mucho tiempo arriba de barcos con la mala suerte de ser abandonado a su suerte en las costas de Caen (Francia). Fue ahí que tuvo su primera instrucción a cargo de jesuitas. Durante la guerra civil inglesa, huye a Holanda por unos años y conoce a Hobbes en París

- A su regreso a UK, inventó un método para escribir duplicado (especie de copia carbónica) pero no tuvo suerte como empresario

Sir William Petty [1623-87]: el primer influencer (cont.)

- Se insertó rápidamente en los círculos intelectuales ingleses –fue uno de los miembros fundadores de la Royal Society y en 1650 le dieron una posición en medicina en Oxford

- Curiosamente o por casualidad su carrera tomó un giro inesperado en 1650 –para bien- cuando se documentó su participación como médico en el caso de la “resurrección” de una mujer condenada a muerte

- Para mayores detalles: Back from the dead

- Finalmente estuvo a cargo de la distribución de tierras en la conquista de Irlanda, previo a un relevamiento territorial que el mismo diseñó

Sir William Petty [1623-87]: el primer influencer (cont.)

Sir William Petty [1623-87]: el primer influencer (cont.)

- Casi todos sus escritos fueron motivados por problemas prácticos de su tiempo y país (imposición, dinero, comercio).

- Si bien era brillante Schumpeter argumenta que no hubo nada muy original o espectacular en sus comentarios; eran similares a la de la clase de economistas que estaban surgiendo

- Sus esquemas y articulaciones no era más sofisticadas que las de sus contemporáneanos

- Pero hubo algo en que se destacó por encima del resto \(\longrightarrow\) tuvo la capacidad de “crear” conceptos y nociones a partir de hechos y los desarrolló mucho más que otros

Sir William Petty [1623-87]: el primer influencer (cont.)

Desarrolló el concepto de velocidad de circulación del dinero.

Concepto de Ingreso Nacional. No se preocupó por la definición pero reconoció su importancia analítica y sus efectos. Entre él y Quesnay están los inicios del análisis moderno del ingreso y cuentas nacionales

‘Father and mother’. Destacó (¿descubrió?) los dos factores originales de la producción

Sir William Petty [1623-87]: método y medición

- En cuanto a su pensamiento en economía, la obra más importante es The Economic Writings of Sir William Petty [Hull (1899)].

- Su principal fama en la época era de ser uno de los fundadores de la estadística (econometría), o como se le llamaba entonces, la aritmética política

- Petty adjudicaba gran valor a la medición cuantitativa (producto de su afinidad con la filosofía baconiana)

- No obstante ello, Petty fue esencialmente un teórico; pero uno cuya definición de hacer ciencia era básicamente enfocarse en medición

- en suma, no concebía la teorización aislada de hechos y descripciones; tomó prestado mucho de este procedimiento de las ciencias físicas

Sir William Petty [1623-87]: método y medición (cont.)

“By Political Arithmetick we mean the art of reasoning by figures upon things relating to government…The art itself is undoubtedly very ancient…[But Petty] first gave it that name and brought into rules and methods” [Davenant (1698), I, p. 128]

Sir William Petty [1623-87]: gastos, impuestos y empleo

- Sus mejores contribuciones están en el libro A Treatise on Taxes and Contributions (1662)

- Menciona los diferentes objetos del gasto (defensa, justicia, instrucción en religión)

- Sugiere el cobro de escuelas y universidades; el cobro de ríos navegables, acueductos, puentes y demás vías de comunicación; y el mantenimiento de húerfanos y pobres en un notable precedente de gasto de asistencialismo

- En un notable espíritu keynesiano, recomienda dar “empleo a los desempleados”

Sir William Petty [1623-87]: gastos, impuestos y empleo (cont.)

…if it be employed to build a useless Pyramid upon Salisbury Plain, bring the Stones at Stonehenge to Tower Hill, or the like; for at worst this would keep their mindes to discipline and obedience, and their bodies to a patience of more profitable labours when need shall require it [Sir William Petty, A Treatise on Taxes and Contributions (1662)]

Sir William Petty [1623-87]: gastos, impuestos y empleo (cont.)

- Defiende la necesidad de los impuestos y su discusión gira alrededor de los impuestos sobre la propiedad

- Elabora un predicción sobre el movimiento y desplazamiento (crecimiento) de las ciudades

before we talk too much of Rents, we should endeavour to explain the mysterious nature of them, with reference as well to Money, the rent of which we call usury; as to that of Lands and Houses afore-mentioned [Sir William Petty, A Treatise on Taxes and Contributions (1662)]

Sir William Petty [1623-87]: gastos, impuestos y empleo (cont.)

- Se explaya sobre diferentes tipos de impuestos \(\longrightarrow\) está en contra de aranceles a las \(M\) excepto en casos que las \(M\) causen “muchos problemas locales”

- Concibió una suerte de “impuesto de capitación” (poll money tax)

I shall speak of Poll-money more distinctly, and first of the simple Poll-money upon every head of all mankinde alike; the Parish paying for those that receive alms, Parents for their children under age, and Masters for their Apprentices, and others who receive no wages [Sir William Petty, A Treatise on Taxes and Contributions (1662)]

Sir William Petty [1623-87]: gastos, impuestos y empleo (cont.)

- Y sigue sobre este tipo de imposición:

The evil of this way is, that it is very unequal; men of unequal abilities, all paying alike, and those who whave greatest charges of Children paying most; that is, that by how much the poorer they are, by so much the harder they are taxed [Sir William Petty, A Treatise on Taxes and Contributions (1662)]

- Finalmente sobre impuestos, recomendó un impuesto al consumo (aunque no un impuesto al gasto personal)

Sir William Petty [1623-87]: valor, renta y excedente

Suppose a man could with his own hands plant a certain scope of Land with Corn, that is could Digg, or Plough, Harrow, Weed, Reap, Carry home, Thresh, and Winnow so much as the Husbandry of this Landr requires; and had withal Seed wherewith to sowe the same. I say, that when this man hath subducted his seed out of the proceed of his Harvest, and also, what himself hath both eaten and given to others in exchange for Clothes, and other natural necessaries; that the remainder of Corn is the natural and true Rent of the Land for that year; and the medium of seven years, or rather of so many years as makes up the Cycle, within which Dearths and Plenties make their revolution, doth give the ordinary Rent of the Land in Corn [Sir William Petty, A Treatise on Taxes and Contributions (1662)]

Sir William Petty [1623-87]:valor, renta y excedente (cont.)

a …collaterall question may be, how much English money this Corn or Rent is worth? I answer, … so much as the money, which another single man can save, whithin the same time, over and above his expence, if he employed himself wholly to produce and make it; viz. Let another man go travel intro a Countrey where is Silver, there Dig it, Refine it, bring it to the same place where the other man planted his Corn; Coyne it, &c. the same person, all the while of his working for Silver, gathering also food for his necessary livelihood, and procuring himself covering, &c. I say, the Silver of the one, must be esteemed of equal value with the Corn of the other: the one being perhaps twenty Ounces and the other twenty Bushels. From whence it follows, that the price of a Bushel of this Corn to be an ounce of Silver [Sir William Petty, A Treatise on Taxes and Contributions (1662)]

Sir William Petty [1623-87]: valor, renta y excedente (cont.)

- Y he ahí basicamente una premonición de la teoría del valor trabajo –Marx le estimaba tanto que consideró a Petty “el padre de la economía política Inglesa

- Y también gran agudeza sobre el valor de metales y las cosas

The world measures things by gold and silver, but principally the latter [Sir William Petty, A Treatise on Taxes and Contributions (1662)]

…is, that all things ought to be valued by two natural Denominations, which is Land and Labour [Sir William Petty, A Treatise on Taxes and Contributions (1662)]

Sir William Petty [1623-87]: valor, renta y excedente (cont.)

[W]e ought to say, a Ship or garment is worth such a measure of Land, with such another measure of Labour; forasmuch as both Ships and Garments were the creatures of Lands and Labours thereupon: This being true, we should be glad to finde out a natural Par between Land and Labour, so as we might express the value by either of them alone [Sir William Petty, A Treatise on Taxes and Contributions (1662)]

- esta es la expresión más cabal de que estuvo increíblemente cerca casi 100 años antes de dar una teoría del valor trabajo de las cosas

Sir William Petty [1623-87]: valor, renta y excedente (cont.)

- Esta idea de relacionar los valores de la tierra (T) y el capital (K) igualando un pedazo de T que produciría “un día de comida de un hombre adulto” al día de trabajo de un ese hombre –’natural Par of Land and Labour.

- Idealmente esto nos daría la unidad de medida a través de la cual reducir las cantidades disponibles de los “dos factores originales”, T y K, a una cantidad homogéneade ‘poder productivo’ que pudiera ser expresado en un número y cuya unidad pudiera expresar un estándar de valor tierra-trabajo.

- Lamentablemente esto no era una explicación del fenómeno del valor, mucho menos una teoría del valor.

Sir William Petty [1623-87]: capitalización y el problema del tiempo

- También se interesó por el problema de la capitalización –tiempo, interés y renta. Está basicamente preguntándose por los precios de los factores

Having found the Rent or value of the usus fructus per annum [of land], the question is, how many years purchase (as we usually say) is the Fee simple naturally worth? [Sir William Petty, A Treatise on Taxes and Contributions (1662)]

- y argumenta que si no hubiera descuento de rentas futuras y la productividad se mantuviera, entonces

Sir William Petty [1623-87]: capitalización y el problema del tiempo (cont.)

then an Acre of Land would be equal in value to a thousand Acres of the same Land; which is absurd, an infinity of unites being equal to an infinity of thousands. Wherefore, we must pitch upon some limited number, and that I apprehend to be the number of years, which I conceive one man of fifty years old, another of twenty eight, and another of seven years old, all being alive together may be thought to live; that is to say, of a Grandfather, Father and Childe; …for if a man be a great Grandfather, he himself is so much the nearer his end, so as there are but three in a continual line of descent usually co-existing together; and as some are Grandfathers at forty years, yet as many are not till above sixty. Wherefore I pitch the number of years purchase, that any Land is naturally worth, to be the ordinary extent of three such persons their lives [Sir William Petty, A Treatise on Taxes and Contributions (1662)]

Sir William Petty [1623-87]: capitalización y el problema del tiempo (cont.)

- Este párrafo es un antecedente increíblemente lúcido en relación al problema financiero y la capitalización

- Es común considerar el límite inferior de la tasa real de interés en un 2% [Cassel (1903)]. Razón \(\longrightarrow\) si cayera por debajo de eso convendría liquidar el capital y hacerlo ingreso en vez de convertir ingreso en capital

- Ciertamente no parece probable que Cassel hubiera leído a Petty salvo que Petty hubiera usado sus habilidades para la resurrección, imposible ciertamente que Petty hubiera leído a Cassel!!!

Sir William Petty [1623-87]: interés y usura

- Directamente relativizó el problema de la usura –como problema moral

As for Usury, the least that can be, is the Rent of so much Land as the money lent will buy, where the security is undoubted; but where the security is causal, then a kinde of ensurance must be enterwoven with the simple natural Interest, which may advance the Usury very conscionably unto any height below the Principal itself [Sir William Petty, A Treatise on Taxes and Contributions (1662)]

Sir William Petty [1623-87]: dinero

- Entendía cómo funcionaba la demanda de dinero

Parallel unto this, is something which we omit concerning the price of Land; for as great need of money heightens Exchange so doth great need of Corn raise the price of that likewise, and consequently of the Rent of the Land that bears Corn, and lastly of the Land it self; as for example, if the Corn which feedeth London, or an Army, be brought forty miles thither, then the Corn growing within a mile of London, or the quarters of such Army, shall have added unto its natural price, so much as the charge of bringing it thirty nine miles doth amount unto [Sir William Petty, A Treatise on Taxes and Contributions (1662)]

Sir William Petty [1623-87]: dinero

- Reconoció las 3 (tres) funciones del dinero: 1) patrón de valor, 2) medio de cambio y 3) depósito de valor. Hizo una analogía muy “médica” del dinero

El dinero es como la grasa del cuerpo político, que si abunda en demasía a menudo impide su agilidad y si es poca significa que está enfermo. Ciertamente, así como la grasa lubrica el movimiento de los músculos, satisface la necesidad de víveres, llena las cavidades desiguales y embellece el cuerpo, así hace el dinero en el Estado, acelerando su acción, suministrandose en el extranjero en época de escasez en el interior, facilita las cuentas en razón de su divisibilidad y embellece al conjunto, aunque especialmente más a las personas que lo poseen en abundancia [Hull The Economic Writings of Sir William Petty (1899)]

Sir William Petty [1623-87]: dinero

- A pesar de que observó correctamente que existía una relación entre la cantidad de dinero y el nivel de actividad económica, no se percató (o al menos no lo expresó) de la relación entre la cantidad de dinero y el nivel de precios

- Si reconoció el concepto de velocidad de circulación del dinero y lo vinculó con la cantidad óptima de dinero

- Consideró correctamente que las prohibiciones de exportar dinero (y de importar mercancias) eran inútiles

Richard Cantillon [1680-1734]

Richard Cantillon [1680-1734]: Vida y obra

- Hasta bien entrado el siglo XX, Cantillon era relativamente poco conocido en relación con otros pensadores económicos

- Sin embargo escribió uno de los primeros y mejores tratados científicos sobre temas económicos \(\longrightarrow\) su Essay on the Nature of Commerce (1755) es mejor como obra analítica que cualquier texto que hayan escrito los Fisiócratas y comparable en algún punto con La Riqueza de las Naciones

- Junto con Petty han sido redescubiertos como “padres” y precursores no oficiales de la economía científica

Richard Cantillon [1680-1734]: Vida y obra (cont.)

- Nació en Irlanda pero se radicó y pasó gran parte de su vida en Francia donde se desempeñó como banquero, uno muy agudo y exitoso para los negocios

- Luego de hacer una fortuna con la burbuja (de bonos) de Mississippi, se dedicó a escribir sus ideas compiladas en el Essay, su única publicación conocida

- buenas razones para suponer que el mérito académico no era la única (o principal) razón para escribir el Essai sino que tal vez desarrolló sus ideas para defenderse legalmente de las acusaciones!

Richard Cantillon [1680-1734]: Vida y obra (cont.)

La Burbuja de Mississippi. La Compañía de Mississippi a cargo de John Law incluia todas las compañías comerciales de Francia en el exterior. En 1720 esta compañía se unió con el Banque Royale, a todos los efectos, el banco central de Francia. La nueva compañía llegó a multiplicar su valor de mercado en 20 veces. Law era un proponente de tasas de interés bajas y abundante cantidad de dinero. El esquema duró 4 años ya que la burbuja explotó –las acciones cayeron 90%!- y la moneda francesa colapsó. Law tuvo que exiliarse. Cantillon, que comprendía perfectamente la fragilidad del esquema, se benefició enormemente de comprar bajo y vender alto. Hizo enemigos en el proceso, fue juzgado, acosado y perseguido políticamente. Murió en circunstancias misteriosas en un incendio en su vivienda –posiblemente asesinado

Richard Cantillon [1680-1734]: Vida y obra (cont.)

- Nació en Irlanda pero se radicó y pasó gran parte de su vida en Francia donde se desempeñó como banquero, uno muy agudo y exitoso para los negocios

- Luego de hacer una fortuna con la burbuja (de bonos) de Mississippi, se dedicó a escribir sus ideas compiladas en el Essay, su única publicación conocida

- buenas razones para suponer que el mérito académico no era la única (o principal) razón para escribir el Essai sino que tal vez desarrolló sus ideas para defenderse legalmente de las acusaciones!

- Los detalles sobre su vida son muy escasos y contradictorios –se dice que llevaba registro “estadístico” de los suelos y sus diferentes composiciones ya que el hombre los “degustaba” (creer o reventar)

Richard Cantillon [1680-1734]: Vida y obra (cont.)

- El Essai de Cantillon es inusual e inédito –no es un compendio de políticas como los tratados fisiocráticos ni tampoco un tratado y una crítica como La Riqueza de las Naciones

- prácticamente a lo largo de todo el texto, es puramente abstracto y desacoplado de lo detalles de la vida real –un tratado puramente analítico

- El Essai está dividido en 3 (tres) partes: 1) un análisis general del funcionamiento de la economía, 2) un análisis de la teoría monetaria y teoría del interés, 3) una discusión del comercio y la banca

Richard Cantillon [1680-1734]: Contribuciones

- Cuestiona a Petty en su optimismo “demográfico” y anticipa a Malthus

Men multiply like Mice in a barn if they have unlimited Means of Subsistence; and the English in the Colonies will become more numerous in proportion in three generations than they would be in thirty in England, because in the Colonies they find for cultivation new tracts of lan from which teyr drive the [inhabitants] [Cantillon, Richard Essay on the Nature of Commerce (1755), pp. 83]

It is also a question outside of my subject whether it is better to have a great multitude of Inhabitants, poor and badly provided, than a smaller number, much more at their ease [Cantillon, Richard Essay on the Nature of Commerce (1755), pp. 83]

Richard Cantillon [1680-1734]: Contribuciones (cont.)

- Escribe sobre valor y riqueza, en línea con los escritos anteriores de Petty y las ideas de la época

The Land is the Source or Matter from whence all Wealth is produced. The Labour of man is the Form which produces it: and Wealth in itself is nothing but the Maintenance, Conveniences, and Superfluities of Life [Cantillon, Richard Essay on the Nature of Commerce (1755), pp. 3]

Richard Cantillon [1680-1734]: Contribuciones (cont.)

- Sobre la cuestión del precio dice

the Price or intrinsic value of a thing [in general] is the measure of the quantity of Land and Labour entering into its production [Cantillon, Richard Essay on the Nature of Commerce (1755), pp. 29]

- Sobre la cuestión de la Paridad que había referido Petty hace una elaboración muy aguda pero entreverada en relación a cómo se asimilan las cantidades de \(L\) y \(T\) en decidir el precio de las cosas

- si uno puede decidir sobre el area de \(T\) que produce la subsistencia de trabajadores que son a su vez necesarios para producir el bien particular

Richard Cantillon [1680-1734]: Contribuciones (cont.)

- Introduce por primera vez el término entrepreneur en sentido técnico

The circulation and exchange of goods and merchandise as well as their production are carried on in Europe by Undertakers and at risk” [Cantillon, Richard Essay on the Nature of Commerce (1755), pp. 29]

- Divide a la sociedad directamente en dos grupos

- aquellos que son contratados a precio fijo (cierto) de antemano (retribución contractual)

- aquellos que no son contratados y que de alguna manera especulan acerca del futuro de los mercados para los cuales producen (retribución incierta)

Richard Cantillon [1680-1734]: Contribuciones (cont.)

- La parte II de su Essai es verdaderamente lúcida y original. Trata primariamente sobre precios, dinero e interés. Su explicación de como se forman los precios de mercado es tal vez la primera referencia en la historia de la economía que describe el mecanismo a través del cual las diferentes disposiciones a demandar y ofrecer terminan produciendo los precios de mercado

- note la brillante descripción en las proximas diapositivas

- Cuando habla sobre el trueque, por ejemplo, nota que una forma de fijar precios de mercado es “are more clever in puffing up their wares, others in running them down”

Richard Cantillon [1680-1734]: Contribuciones (cont.)

Several maitres d’hotels [at Paris] have been told to buy green Peas when they first come in. One Master has ordered the purchase of 10 quarts for 60 livres, another 10 quarts for 50 livres, a third 10 for 40 livres and a fourth 10 for 30 livres. If these orders are to be carried out there must be 40 quarts of gren Peas in the Market. Suppose there are only 20. The Vendors, seeing many Buyers, will keep up their Prices, and the Buyers will come up to the Prices prescribed to them: so that those who offer 60 livres for 10 quarts will be the first served. The Sellers, seeing later that no one will go above 50, will let the other 10 quarts go at that price. Those who had orders not to exceed 40 and 30 livres will go away empty [Cantillon, Richard Essay on the Nature of Commerce (1755), pp. 119-120]

Richard Cantillon [1680-1734]: Contribuciones (cont.)

If instead of 40 quarts there were 400, not only would the maitres d’hotels get the new Peas much below the sums laid down for them, but the Sellers in order to be preferred one to the other by the few Buyers will lower their new Peas almost to their intrinsec value, and in that case many maitres d’hotels who had no orders will buy some [Cantillon, Richard Essay on the Nature of Commerce (1755), pp. 120-121]

Richard Cantillon [1680-1734]: Contribuciones (cont.)

- Discutió las rentas que debía obtener (y el destino que debía dar) el agricultor

It is the general opinion in Englad that a Farmer must make three Rents. (1) The principal and true Rent which he pays to the propietor, supposed equal in value to the produce of one third of his Farm, a second Rent for his maintenance and that of the Men and Horses he employs to cultivate the Farm, and a third which ought to remain with him to make his undertaking profitable [Cantillon, Richard Essay on the Nature of Commerce (1755), pp. 121]

Richard Cantillon [1680-1734]: Contribuciones (cont.)

- Define y caracteriza los diferentes usos del dinero. Considera demanda de dinero para resguardarse de riesgos potenciales (demanda precautoria)

- Considera también la influencia de los hábitos cambiantes de terratenientes y de los vendedores para explicar cambios en la demanda de dinero

- Observa que la existencia de bancos economiza la demanda de dinero e incrementa la circulación (menos dinero, más rápida circulacion)

Richard Cantillon [1680-1734]: Contribuciones (cont.)

- Discutió las rentas que debía obtener (y el destino que debía dar) el agricultor

M. Locke lays it down as a fundamental maxim that the quantity of produce and merchandise in proportion to the quantity of money serves as the regulator of Market price. I have tried to elucidate his idea in the preceeding Chapters: he has clearly seen that the abundance of money makes everything dear, but he has not considered how it does so. The great difficulty of this question consists in knowing in what way and in what proportion the increase of money raises prices [Cantillon, Richard Essay on the Nature of Commerce (1755), pp. 161]

Richard Cantillon [1680-1734]: Contribuciones (cont.)

- Examina las formas y mecanismos en que el dinero se esparce en la comunidad

- argumenta que la forma en que los aumentos en la cantidad de dinero impactan en los precios dependen de a qué manos llega el dinero primero

- Si llega primero a quienes tienen baja \(M^{d}\), entonces circula rápidamente y precios aumentan rapido

- Si llega primero a quienes acumulan dinero, entonces los precios no aumentan (o aumentan menos)

- no obstante reconoce que aún en este caso los precios terminarían aumentando eventualmente [NOTA: compare con aumentos de P post-Covid-19 en países avanzados]

Richard Cantillon [1680-1734]: Contribuciones (cont.)

- Y concluye sobre la relación entre aumentos en cantidd de dinero y aumentos en precios:

From all this I conclude that by doubling the quantity of money in a State the prices of products and merchandise are not always doubled. A River wich runs and winds about in its bed will not flow with double the speed when the amount of its water is doubled [Cantillon, Richard Essay on the Nature of Commerce (1755), pp. 177]

Richard Cantillon [1680-1734]: Contribuciones (cont.)

- También escribió sobre el tema del interés y su determinación. Definitivamente ataca la visión de que es la cantidad de dinero la que afecta la tasa de interés –ofrece contraejemplos apoyando su punto

- Y aquí es donde introduce su análisis del mercado de dinero en relación al mercado de fondos prestables tomando en cuenta su alta complejidad

- distingue entre préstamos para consumo y préstamos “para negocios” (inversión)

- Finalmente uno de los pocos párrafos no analíticos y críticos hacia la praxis de la política

Richard Cantillon [1680-1734]: Contribuciones (cont.)

It is then undoubted that a Bank with the complicity of a Minister is able to raise and support the price of public stock and to lower the rate of interest in the State at the pleasure of this Minister when the steps are taken discreetly, and thus pay off the State debt. But these refinements which open the door to making large fortunes are rarely carried out for the sole advantage of the State, and those who take part in them are generally corrupted. The excess banknotes, made and issued on these occasions, do not upset the circulation, because being used for the buying and selling of stock they do not serve for household expenses and are not changed into silver. But if some panic or unforeseen crisis drove the holders to demand silver from the Bank, the bomb would burst and it would be seen that these are dangerous operations [Cantillon, Richard Essay on the Nature of Commerce (1755), pp. 323]

Los fisiócratas: la primera “escuela”

El contexto de Francia en siglos 17 y 18

- La aparición sistemática del análisis económico se ve no sólo de manera primitiva en Petty y Cantillon sino también y de manera más elocuente en los escritos de los economistas franceses que serían conocidos como los fisiócratas

- Las condiciones en Francia durante el siglo 17 y principios del 18 era brutales para la gran mayoría de sus habitantes \(\longrightarrow\) la pobreza era extrema y agonizante

- El texto The Characters de La Bruyere describe que “en la campiña podían observarse animales débiles y maltratados, aparentemente despreocupados por lo que crecía en los alrededores, y de repente una de las criaturas alza la mirada –sorpresa, es un hombre!”

- La guerra, los impuestos y los privilegios a los ricos habían devastado al pueblo

El contexto de Francia en siglos 17 y 18 (cont.)

- La política comercial (y la mayoría de la política económica) estaba en manos del infame Colbert –el superministro de Luis XIV

- hay una descripción imperdible de Colbert en La Riqueza de las Naciones que lo ve como un hombre recto, de experiencia y uno que ha “adquirido todos los prejuicios del sistema mercantil”

- Este contexto era básicamente lo que enfrentaban los economistas franceses de la epoca cuando escriben

Críticos de políticas y de sistemas

- Uno de los principales ataques a las políticas y al sistema mercantil fue la de Boisguillebert (1646-1714)

- Era un juez que escribió Detail de la France en el que ataca al colbertismo en el punto en que privilegiaba las manufacturas en desmedro de la agricultura (la principal ocupación de las mayorías)

- Argumentó que la verdadera naturaleza de la riqueza nacional estaba en los bienes y servicios y no en el dinero

- Fustigó el opresivo sistema impositivo –la taille (\(T\) a la propiedad), las aides (\(T\) a las ventas) y las douanes (\(T\) al comercio exterior)

Francois Quesnay [1694-1774] y sus discípulos

- En la primera mitad del siglo 18 hubo muy poca discusión y debate sobre cuestiones económicas –entre otras cosas ayudado por la fenomenal debacle del esquema Mississippi y del colapso de la economía francesa; hubo algunos autores como Melon, Dutot y hasta el mismo Montesquieu con ideas economicas aisladas

- Pero entre 1750 y 1760, florecieron los escritos y especulaciones económicas de la mano de los fisiócratas –el Dr Quesnay y sus amigos

- Hubo contribuciones importantes de los fisiócratas –pero posiblemente no al nivel de Cantillon, Hume o Smith

Francois Quesnay [1694-1774] y sus discípulos (cont.)

Gentlemen, we have lost our master, the veritable benefactor of humanity belongs to this earth only by the moemory of his good deeds and the imperishable record of his achievements. Socrates has been said to have brought down morality from the skies. Our master has made it germinate upon earth. Celestial morality was a guide only for a few chosen souls. The doctrine of the net product procures subsistence for the children of men, secures them in its enjoyment from violence and fraud, lays down the principles of its distribution and assures its reproduction. O bust! O venerable bust that represents to us the features of our common master. It is before you, it is to the vow of universal fraternity which our conscience, enlightened by the teaching of the excellent man whom you portrayed for us bids us observe. O Master, look down from your heavenly heights. Smile still on our words and works and our tears, while my trembling hand offers on your tomb laurels which will never perish [Marquis Mirabeau, Eulogy on the Funeral of Francois Quesnay (1774)]

- No cabe duda de la ornamentación y dramatismo francés viendo cómo despiden a uno sus pensadores!

Francois Quesnay [1694-1774] y sus discípulos (cont.)

- Francois Quesnay [1694 fue el líder y figura intelectual indiscutida de los fisiócratas. Nació en el seno de una familia humilde, dedicada a la agricultura

- Se convirtio en cirujano y luego devino en médico por problemas de visión

- Una de sus principales obras On the Circulation of Blood

- Se mantuvo en los más altos círculos políticos y sociales, residía en Versalles

- Fue el asistente personal de Madame de Pompadour (la amante del rey!)

Francois Quesnay [1694-1774] y sus discípulos (cont.)

- Se interesó por la agricultura y particularemnte en avances técnicos. Por lo anterior, había obtenido fortuna y adquirido tierras. Escribió algunos articulos breves y esto lo fue conduciendo al análisis económico más general y su creación más famosa –el Tableau Economique –no sobre la circulación de la sangre sino de la riqueza!

- Quesnay probablemente hubiera sido una figura aislada (al igual que Cantillon) si no hubiera sido por sus continuadores –Mirabeau quien era extremadamente social lo popularizó y formó una escuela de seguidores

Francois Quesnay [1694-1774] y sus discípulos (cont.)

- El rasgo distintivo más importante de los fisiócratas era su posición pro-agricultura (y por añadidura anti-promoción de las manufacturas)

- Un segundo rasgo es que su actitud frente al Gobierno era una de relativo laissez-faire

- Tercero, la filosofía de los fisiócratas no era utilitarista en el sentido en que podemos decir que la de Smith y Hume lo era

- descansaba mas bien en una concepción bastante simplista de la ley natural

- “You simply obey the laws of nature” parece haber sido una respuesta común a muchas inquietudes

- lecturas de los textos fisiocráticos revelan el lugar de primacía que le asignaban a la ley natural

Francois Quesnay [1694-1774] y sus discípulos (cont.)

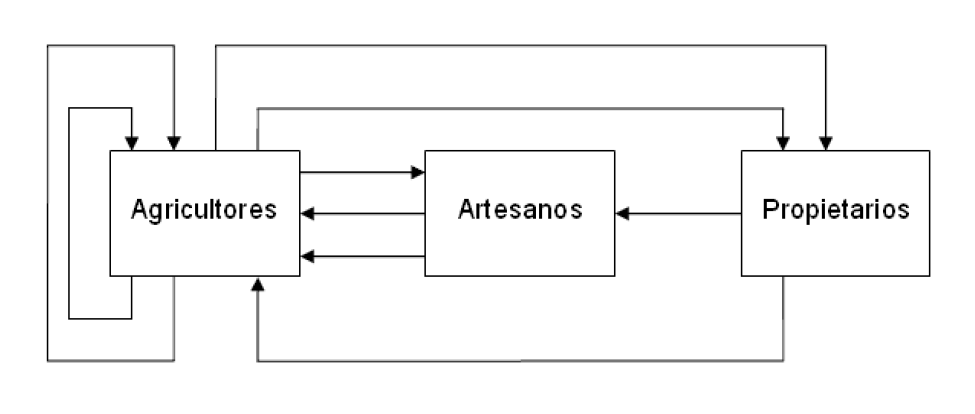

- Produjeron una clasificación (tipificación) de los miembros de la sociedad

- sólo la agricultura era productiva

- No negaron la importancia de otros tipos de trabajo (sectores) pero distinción analítica entre trabajo productivo y trabajo improductivo (o estéril)

- Las clases productivas consistían en: agricultores y terratenientes (propietarios); los artesanos eran la clase estéril

- Terratenientes eran productivos por su contribución de adelantos (capital) que hacían fértil la tierra \(\longrightarrow\) por ello recibían el producto neto (produit net)

- Trabajadores aplicaban su trabajo a la tierra y cobraban salarios de subsistencia

Francois Quesnay [1694-1774] y sus discípulos (cont.)

- Esta idea tenía un fundamento \(\longrightarrow\) los terratenientes eran los responsables de todo impuesto y que el resto de impuestos debía abolirse

- En base a su clasificaicón erigieron una teoría de la distribución

- los trabajos de las clases productivas se concebían como un flujo anual

- el flujo anual se distribuía entre aumentos en los adelantos a las clases productivas y compras a las clases no productivas

- Idea fundamental \(\longrightarrow\) compras (pagos) a las clases no productivas no interfieran con adelantos a los agricultures – recuerde que todos estos pagos salían del produit net

- Si este era el caso entonces el producto neto sería menor y la economía empeoraría

Francois Quesnay [1694-1774] y sus discípulos (cont.)

Francois Quesnay [1694-1774] y sus discípulos (cont.)

Francois Quesnay [1694-1774] y sus discípulos (cont.)

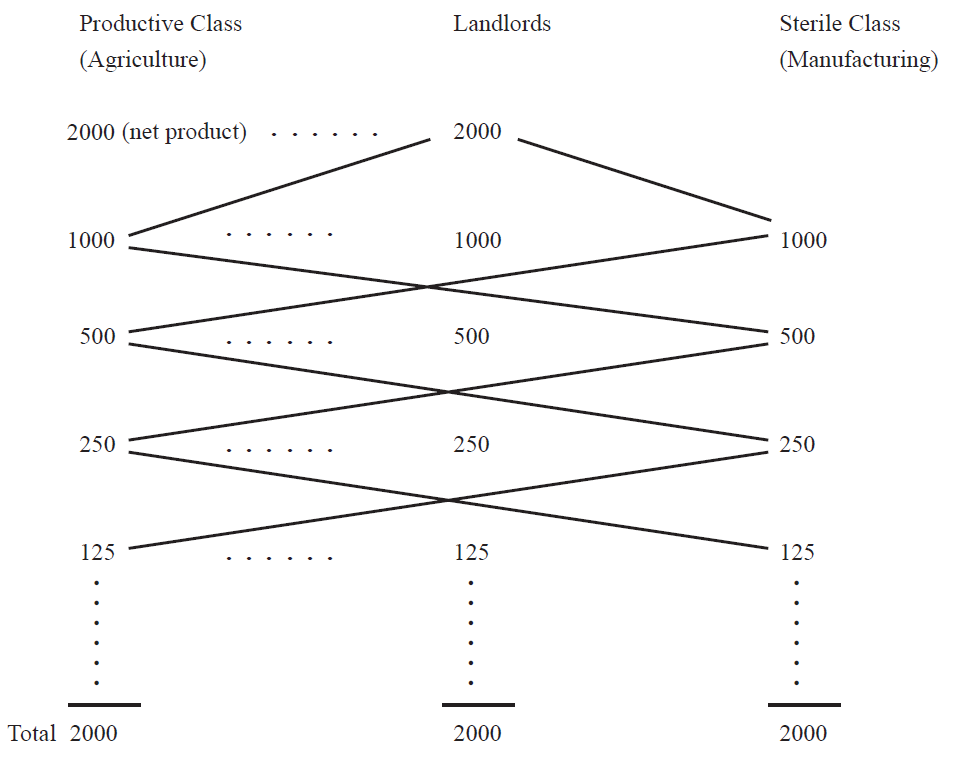

- La idea de un flujo anual de producción y su consecuente distribución está contenida en el famoso Tableau Economique en la figura anterior

- Existen 3 (tres) columnas: 1) la clase productiva de los agricultores, 2) la clase terrateniente que recibía el produit net y 3) la clase estéril

- Se parte de un produit net (terratenientes) y se va distribuyendo entre clase productiva (agricultores) y estéril (manufacturas)

- cada una de estas clases gasta ese ingreso entre clase productiva y clase estéril –los agricultures usan los 1000 para comprar 500 a si mismo (insumos y materiales) y 500 a la clase estéril

Francois Quesnay [1694-1774] y sus discípulos (cont.)

El Tableau Economique. Terratenientes gastaban 1000 en la clase productiva y 1000 en la clase estéril; la clase estéril gastaba 500 en los productos de la clase productiva y 500 en los productos de la clase estéril. Y así sucesivamente. Este es un esquema estático en el sentido que se realiza cada año con la idea de mantener -periodo tras periodo- el flujo anual del produit net. Con este diagrama, los fisiócratas podían inferir si las sociedades estaban avanzando o declinando. Y de este diagrama dedujeron que todos los impuestos deberían recaer en el produit net –debían eliminarse todos los impuestos intermedios.

Francois Quesnay [1694-1774] y sus discípulos (cont.)

- ¿Era sólo semántica la distinción entre clases y roles? La intuición es que no y que los fisiócratas entendían que sólo el producto de la agricultura y la extracción producían un excedente \(\longrightarrow\) sólo estos producían nuevas riquezas

- el resto de los trabajos sólo cubrían sus costos de producción

- Adam Smith luego criticaría pero retendría la distinción entre trabajo productivo e improductivo

- pero la distinción era entre trabajo que dejaba algo en términos de acumulación (capital) y aquel no

- En el caso de Smith el trabajo improductivo no agregaba riqueza en el sentido de riqueza de capital \(\longrightarrow\) bastante más relevante que la distinción de los fisiócratas

Francois Quesnay [1694-1774] y sus discípulos (cont.)

- Un punto importante es que los fisiócratas crearon un sistema de análisis \(\longrightarrow\) el Tableau Economique no es otra cosa que un sistema de relaciones

- el mérito principal es que se dieron cuenta de que mirando al sistema en general podían explicar variaciones en las relaciones del sistema como un todo

- Otro mérito fue que no sólo vieron al sistema interconectado en un momento del tiempo sino también interconectado a través del tiempo

- el foco estaba puesto no en la riqueza per se sino en la circulacíon de la riqueza!

Francois Quesnay [1694-1774] y sus discípulos (cont.)

¿Cuál es el status del Tableau Economique en la HPE? Adam Smith pensaba que estaba basado en una falacia –la división “factica” de clases no solamente verbal. ¿Es un precedente de Walras y su sistema de equilibrio general? No, al menos en las características esenciales del sistema walrasiano. El sistema fisiocrático no era un sistema estable –no había ni mecanismo ni fuerzas que garantizaran equilibrio. No hay relación entre precios relativos y producción/distribución de recursos. Tampoco guarda relación con el sistema keynesiano –hay un precedente de flujo circular gasto-ingreso pero no multiplicador. Tampoco relación con dinámica post-keynesiana –no es un sistema dinámico genuino más bien la dinámica se introduce a partir de estática comparativa entre períodos

Francois Quesnay [1694-1774] y sus discípulos (cont.)

- Tal vez una opinión justa y mesurada es que el Tableau Economique puede ser reescrito como un sistema de Leontief –matriz insumo-producto.

- Tampoco fueron un precedente de teorías primitivas de sub-consumo \(\longrightarrow\) sólo puede decirse que se opusieron a consumos de lujo si interferían con el mantenimiento del produit net

La simple y accesibilidad de Turgot [1727-1781]

- Fue de hecho Turgot quien definió las dos clases como las de “los Cultivadores –clase productiva- y la de los Artesanos –clase estipendiaria.”

- En cierta manera, Turgot tuvo la característica de escribir en un lenguaje mucho más común que era el lenguaje típico de Quesnay y los fisiócratas

- en efecto, Turgot era amigo de los fisiócratas y escribió en la misma linea

- Escribe sobre la importancia de la tierra, la desigualdad en su distribución y las diferentes clases

La simpleza y accesibilidad de Turgot [1727-1781] (cont.)

There is another way of being wealthy without working and without possessing land of which I have not yet spoken. It is necessary to explain its origin and its relation with the rest of the system of the distribution of wealth in society, of which I have just sketched the outlines…Each commodity can serve as a scale or common measure with which to compare the value of all others [Turgot Reflections on the Formation and the Distribution of Wealth (1770), pp. 134-135]

La simpleza y accesibilidad de Turgot [1727-1781] (cont.)

- La obra e ideas de Turgot realmente son interesantes. En cierta manera, simplifican, aclaran y amplian algunas de las ideas de Quesnay

- Turgot escribió sobre la moneda ideal y las funciones del dinero para facilitar la separación de diferentes trabajos

- Habla sobre la “reserva del producto anual, acumulado para formar capitales” y sobre “la necesidad de adelantos en la agricultura” antes de generar el produit net

- empleos de adelantos pueden ser ya bien en “compra de tierras” o también en “adelantos para manufacturas y emprendimientos industriales”